|

|

|

|

|

|

2090-2110

Photosynthetic humans

Following many decades of research, a number of human-plant chimeras are moving from the laboratory into clinical and commercial use. Among the treatments now available is a method for combining the photosynthetic capabilities of chloroplasts with human skin. This enables a person to gain energy from being exposed to sunlight.

In 1990, scientists first coined the term "kleptoplasty" to describe a symbiotic phenomenon whereby plastids, notably chloroplasts from algae, are sequestered by host organisms. This had been observed in Elysia chlorotica, a species of green sea slug that absorbed chloroplasts from the algae it ate, making it effectively a solar-powered animal.

In the early decades of the 21st century, researchers engineered cells that combined both animal and human material, producing chimeras (named after the creature from Greek mythology that possessed the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a snake). One notable experiment, for example, succeeded in placing human stem cells into a pig embryo, albeit with very low efficiency. Another study a few years later placed human stem cells into monkey embryos, observed over a 20-day period.

These and other studies paved the way to growing animals with human organs – addressing the shortage in transplantable hearts, kidneys, livers, lungs and other body parts – while also helping researchers to understand more about early human development and disease progression.

Alongside these human-animal chimeras, progress occurred with engineering the first human-plant chimeras. Researchers had earlier demonstrated the synthesis of whole genomes from scratch, such as the recoding of 18,214 codons in E. coli to produce a new variant of the bacteria. This led to larger and more complex genomes being synthesised. Further developments lay ahead, as the full potential of this field started to become apparent. No longer limited to just genomes, researchers began to explore the creation of entire organelles – specialised subunits like "mini-organs" within a cell. The first synthetic chloroplasts emerged as lab teams aimed to improve upon the efficiency of natural ones, with a longer-term goal of replicating the process seen in the green sea slug Elysia chlorotica.

Following the creation of these synthetic organelles, work proceeded on merging them with human skin cells. Integrating this hybrid "second skin" into subcutaneous layers and the body's circulatory system became an even greater challenge, though the powerful AIs now emerging helped to accelerate the research process.

By the end of the 21st century and early 22nd,** the technique is becoming viable for clinical and commercial applications. Biotechnology upgrades in general are increasing in popularity during this period, as transhumanism continues its shift from a minority to the wider population. For those unable or unwilling to undergo the full procedure, less invasive options are available – such as photosynthetic hair, providing a small energy boost during the day. These hairs can be kept the same green as chlorophyll, or tweaked to a different colour.

For the more adventurous types, a whole-body infusion can provide an entire outer layer of photosynthetic skin. In other words, the equivalent of a solar panel with a surface area of nearly two square metres. To gain the full benefits, however, the second skin must be engineered to be at least 300 times more efficient than natural chloroplasts.* On an ideal day with plentiful sunshine, this can generate enough energy in one hour to meet their body's needs for up to 24 hours, depending on how fully clothed they are. Akin to a lasting caffeine rush,* the sensation of being charged with solar power is especially useful for those who may suffer with chronic fatigue or similar health issues.

As with hair, this second skin can be kept green, or modified to a more natural human colour. Most people keep their original skin tone, but green is a more popular choice with certain subcultures and eccentric personalities.

2090

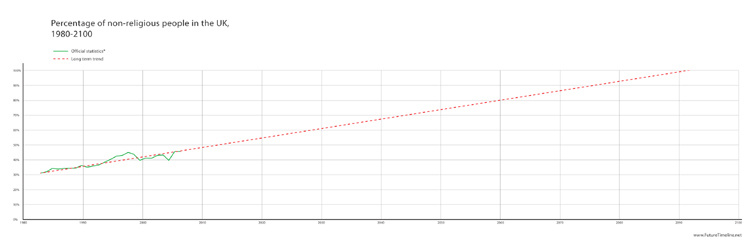

Religion is fading from European culture

In some European nations, the number of people considering themselves to be non-religious has increased from around 30% in 1980, to over 90% now.* Although large numbers of Muslims populate the continent, a substantial portion are now only "culturally" Muslim, rather than having a literal interpretation of the Koran. Mainstream Islam has begun a reformation and modernisation in recent years – aided by improvements in education, combined with the broad homogenisation of culture resulting from globalisation, the Internet, international agreements and other factors.

Medical advances are undermining religion as a whole, by greatly diminishing the fear of death, while developments in AI, robotics and biotechnology are beginning to trivialise the miracles on which many ancient religions are based. The increasing presence of androids in society – along with other forms of sentience – is adding a whole new dimension to the way humans view themselves and their place in the Universe. The ability to communicate with certain artifically enhanced animals (such as dolphins, monkeys and domestic pets) is also contributing to this trend.

Spirituality continues to play a role in European cultures – but is now based more on nature and physical reality, rather than myths, dogma or supernatural forces.

The USA still lags behind Europe in terms of atheistic belief, however. It will be another century before America reaches the same level; even longer for certain parts of Asia. Even then, a small percentage of citizens will continue to worship a God (or Gods), well into the next millenium. These people will tend to be those who reject science and technology, or have purposefully chosen to isolate themselves from the rest of the world.

Click to enlarge.

Hypersonic vactrains are widespread

Much of the world has now established a hypersonic, evacuated tube transport system connecting major population centres.* Its routes extend primarily throughout Russia, Northern Europe, Canada and the US. These trains are more advanced versions of the slower, simpler prototypes first introduced decades previously.*

This form of transport works by combining the principles of maglev trains and pneumatic tubes. The trains, or vactrains as they are called, travel inside a closed tube, levitated and pushed forward by magnetic fields. After passing through an airlock, the train cars enter a complete vacuum inside the tube. With no air friction to slow it down, the vactrain can reach speeds far beyond that of any traditional rail system. The fastest routes can now reach speeds of around 4,000 mph (6,400 km/h)* – around five times the speed of sound – compared to a 300 mph maglev train a century earlier.*

With speed of this magnitude, any city within the network can be reached in just a few hours, even if located on the other side of the planet. A number of new routes are in the planning stages as well, including a system of truly massive transoceanic connections. This is possible thanks in part to the relative cheapness (10% the cost of high-speed rail), as well as its energy efficiency. Since the train cars simply coast for most of the trip after being accelerated, slowing down also allows most of the energy to be regained by the track system. The modular design of tubes enables construction to be automated.

One of the main issues designers had to contend with was the problem of safety. At such high speeds, even the slightest bump in the track or misalignment could end in disaster. In addition, the sheer size of the tube systems means that engineers have to deal with the movements of tectonic plates – a particular problem when crossing fault lines. In order to deal with this and disasters such as earthquakes, an immense system of gyroscopes and adjusters are maintained along the length of each route. These are controlled by an automated system of computers receiving constant streams of weather and seismic data, adjusting and bracing the track in real time. Leaks into the vacuum are managed through a combination of self-healing materials and redundant plating.

The late 21st century is a bleak, fragile time for humanity, with much rebuilding to do. However, the resurgence of international travel (following a collapse in earlier decades) is contributing once more to a homogenization between stable countries, with ease of transport bringing the world closer together. One particular area in which this helps is for rapid movement and resettling of refugees affected by climate-related disasters.

Bowel cancer is effectively eradicated in developed countries

By 2090, bowel cancer has all but vanished as a cause of death in the developed world.* The age-standardised mortality rate (ASR), once stubbornly high at 14 per 100,000 in the early 1980s, fell below 10 in the 2010s and dropped under 1 by 2063. After further steady declines, it now stands below 0.01 per 100,000. This disease, which killed nearly a million people annually in the 2020s, now exists only as a clinical anomaly – a handful of mutation-driven cases that clinicians treat swiftly and curatively.

Earlier decades provided the foundation for this achievement. Routine, population-wide use of molecular diagnostics became standard by the mid-21st century. Personalised vaccines, custom-designed for each patient's tumour profile, primed the immune system to eradicate cancer cells with transformative efficacy. Alongside this, genetic editing tools advanced to the point of routinely repairing precancerous mutations before they gave rise to tumour growth, first protecting high-risk patient groups and later extending to the wider population as a routine safeguard against future disease.

In subsequent decades, nanotechnology matured into clinical nanorobotics, enabling cellular-scale surgery that repaired or removed malignant tissue without collateral damage. Meanwhile, artificial general intelligence (AGI), combined with quantum-enhanced computing, simulated trillions of molecular interactions within minutes and generated adaptive treatment protocols that updated in real time as tumours evolved. These technologies allowed oncologists to remain perpetually one step ahead.

At the same time, public health campaigns transformed diets, cut smoking and alcohol consumption, and encouraged active lifestyles. Environmental regulations curbed exposure to carcinogenic chemicals, lowering population-level risks even further.

Bowel cancer, once among the world's most common and deadly malignancies, now stands as a historical footnote in developed countries. While inequalities persist in some regions, with slower access to advanced care, the overall global burden has plummeted. With formerly common killers such as lung, bowel, liver, brain, and other cancers now vastly diminished, humanity has defeated nearly all of the solid tumours that once claimed millions of lives. Only a small group of particularly resistant cancers – such as pancreatic – remain as outliers, and even these are now in visible decline.

2091

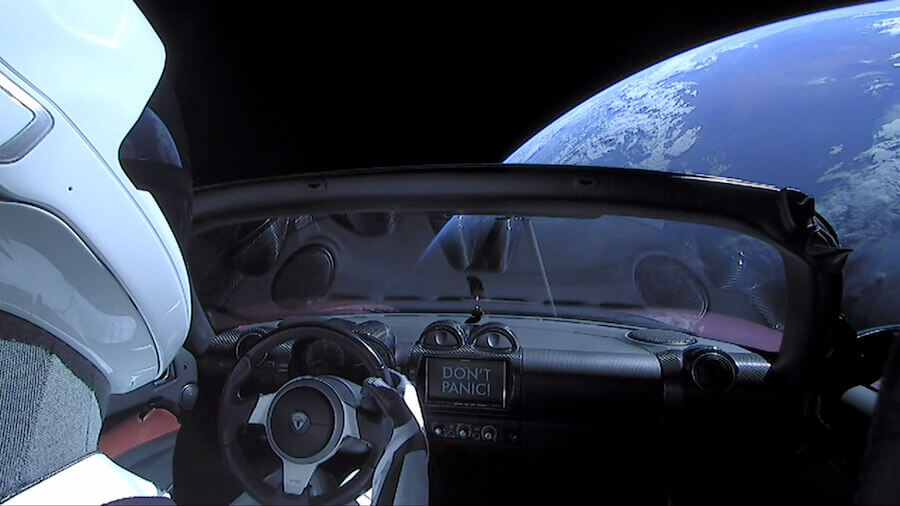

SpaceX's "Starman" has a close encounter with Earth

On 6th February 2018, U.S. aerospace company, SpaceX, conducted the maiden launch of the Falcon Heavy, a partially reusable heavy-lift launch vehicle designed to transport people and cargo beyond Earth orbit.* The rocket was carrying a Tesla Roadster, which belonged to SpaceX founder Elon Musk, as a dummy payload. Inside the electric sports car was a mannequin, nicknamed Starman, who appeared to "drive" the car while wearing a spacesuit.

The Roadster, released upon reaching outer space, had sufficient velocity to escape Earth's gravity. It entered into an elliptical heliocentric orbit that would eventually cross the orbit of Mars, reaching a maximum distance from the Sun at aphelion of 1.66 AU. In 2091, after a period of 73 years, Starman returns to cislunar space and makes a close approach of Earth.* He continues to circle the inner Solar System for millions of years into the future, with a small probability of colliding with Earth (6%) and Venus (2.5%) during the first million years.

Credit: SpaceX

2092

West Antarctica is among the fastest developing regions in the world

As a result of global warming, temperatures at the poles have risen more than anywhere else in the world – meaning that parts of Western Antarctica are now comparable with the climates of Alaska, Iceland and northern Scandinavia. In some areas, melting of surface ice has resulted in conditions appropriate for large-scale human settlement.* The icy continent today would be unrecognisable to observers from the 20th century: its northern peninsula is now home to numerous towns and conurbations, with a total population numbering in the millions. Even farming and crop growing is now possible in some of the most northerly areas, using genetic modification techniques.

Rapid immigration from countries all over the world has created a diverse mixture of people and cultures flocking to this new land of opportunity. In a way, the settlement of Antarctica is similar to that of America in the 18th and 19th centuries. The highest density cities are becoming cultural melting pots similar to London and New York, though on a smaller scale.

© Luca

Oleastri | Dreamstime.com

2095-2100

Hurricane defence fields are operational in the U.S.

Compared to other forms of energy production, offshore wind power emerged relatively late in the modern era. Although land-based turbines had been around for centuries in some form, their offshore equivalents did not arrive until the end of the 20th century. The first commercial offshore wind farm was constructed in Denmark in 1991 and consisted of 11 units generating less than five megawatts (MW). The project was viewed with scepticism at the time, but the experience it provided led to cheaper and more efficient designs. Despite some downsides, offshore wind proved to have the major advantage of capturing much stronger and more persistent winds at sea. It could also be sited close to load centres along coasts, such as large cities, thus eliminating the need for new long-distance transmission lines. Furthermore, NIMBY opposition to construction was usually much weaker.

Following the first installation at Denmark, more projects began to spring up around Europe in the 1990s. However, it remained a niche industry and would not take off until the early 21st century. The UK opened its first offshore wind farm in 2000, which had a modest capacity of just 4MW, but then rapidly developed much larger projects, overtaking Denmark to become the world leader by 2008. It also became home to the single largest project in the world – the 175-turbine London Array – completed in 2013. Europe as a whole boasted 11GW of capacity by 2015, more than 90% of the global total.

America lagged far behind Europe. A small, experimental floating wind turbine – the 20 kilowatt Volturn US – was demonstrated in the Penobscot River, Maine, during 2013. The nation's first commercial offshore wind farm – the 30MW Block Island project at Rhode Island – finally began operation in 2016. These small beginnings were just a precursor, however, to a period of tremendous expansion.*

A number of states were setting highly ambitious targets for the years and decades ahead. The state of New York established a goal of 2,400MW to be completed by 2030. The neighbouring state of New Jersey aimed for 3,500MW by that same date. In 2016, an update to Massachusetts energy law committed the state to purchasing 1,600MW of offshore wind by 2027. Other states followed, launching plans for development around the Gulf Coast and Pacific west coast, as well as the Great Lakes region. Some 30 offshore wind farms totalling 24GW of capacity were now in planning.*

Offshore wind, like solar power, was poised to become one of the exponential growth industries of the 21st century. The U.S. Department of Energy estimated that the country had a gross resource potential of 10,800GW and a "technical" resource potential of 2,058GW – enough to power the whole of the United States. More and more projects were getting underway as developers realised the economic, social and environmental benefits of this abundant form of energy.

A setback occurred when the U.S. Navy placed restrictions on large areas of Pacific coastline – including all of San Diego and Los Angeles, extending up to the Central Coast. While this did not completely stymie the offshore wind industry in that part of America, it made the North and South Atlantic states a generally more attractive bet for investors.* These places had much larger and easier to access wind resources in any case.*

Improvements in technology and cost, alongside increasing concerns about climate change, led to renewables playing a greater and greater role in the energy mix of the United States. By 2050, the nation was generating more than 86GW of electricity from offshore wind.* The South Atlantic states, continuing the trend from earlier years, experienced particularly strong growth. These had the largest technical resource potential of any coastal region: nearly 30% of the U.S. total. With fossil fuels now rapidly heading for obsolescence – and next-generation turbines being deployed in enormous numbers – the second half of the 21st century would provide even greater opportunities for expansion.

Advances in wind technology continued to reduce the cost, while boosting the efficiency, scalability and durability of turbines. Powerful artificial intelligences were now emerging to handle the planning, construction, operation and maintenance of wind farms, using vast teams of robots, drones and other automated systems.

Among the most promising breakthroughs were floating platforms, which allowed turbines to be sited further out to sea (rather than needing part of their structure to be anchored in the sea floor). This had been a niche sector throughout the 2020s, but became cost-competitive during the 2030s and grew markedly from that decade onwards.* Another design that became popular was ice-resistant floating technology. While not particularly useful in the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico or Pacific, it helped to increase the resource potential of the Great Lakes region, making projects there more adaptable and sturdy.

New super-strong but lightweight materials were enabling wind turbines to reach great sizes. From a few tens of metres in the 1990s, they increased to heights of 260 metres (853 feet) by 2021 and then grew even taller over subsequent decades. This was accompanied by an order of magnitude boost in their capacities, allowing tens of megawatts for a single turbine.

During the second half of the century, wind farms established in the Atlantic became so large and widespread that some began to merge and combine to form gigantic networks spanning hundreds of miles. What had seemed like "megaprojects" back in 2050 were being dwarfed in scale by the new proposals organised by super-intelligent AI, which had an increasingly strong pull on the reins of the economy. Initially serving in a mere advisory role, these sentient programs were gaining ever more control in terms of energy and resource utilisation. Their capabilities were becoming strong enough to reshape not just the political and economic sphere, but the physical and natural systems of Earth itself. Recognising the existential threat of climate change, the AIs began to implement one of their most important long-term plans.

By 2100, the South Atlantic states are generating over 300 gigawatts of offshore wind power – fully half of their technical resource potential. In addition to providing abundant clean energy, these vast networks now serve an incredibly important extra function: the sheer scale of wind farms now spread across the coasts is sufficient to interact with and alter the strength of approaching hurricanes.

After using satellites to analyse wind patterns, thousands of floating platforms are manoeuvred by AI to their optimal positions. The energy extracted by these wind turbines, when fully optimised, can diminish a hurricane's peak wind speed by over 90 mph (148 km/h) – enough to reduce it from category 5 to category 1 or less – and reduce storm surges by almost 80%.**

These hurricane defence fields are not infallible and many other impacts of climate change remain to be solved. Nevertheless, the ability to partially control an aspect of the world's weather system is hailed as a major milestone in the fight against global warming. From a historical perspective, it represents a significant step towards humanity becoming a Type 1 civilisation on the Kardashev scale.* Other regions are taking similar measures too – such as the typhoon-hit nations of Southeast Asia.

2095

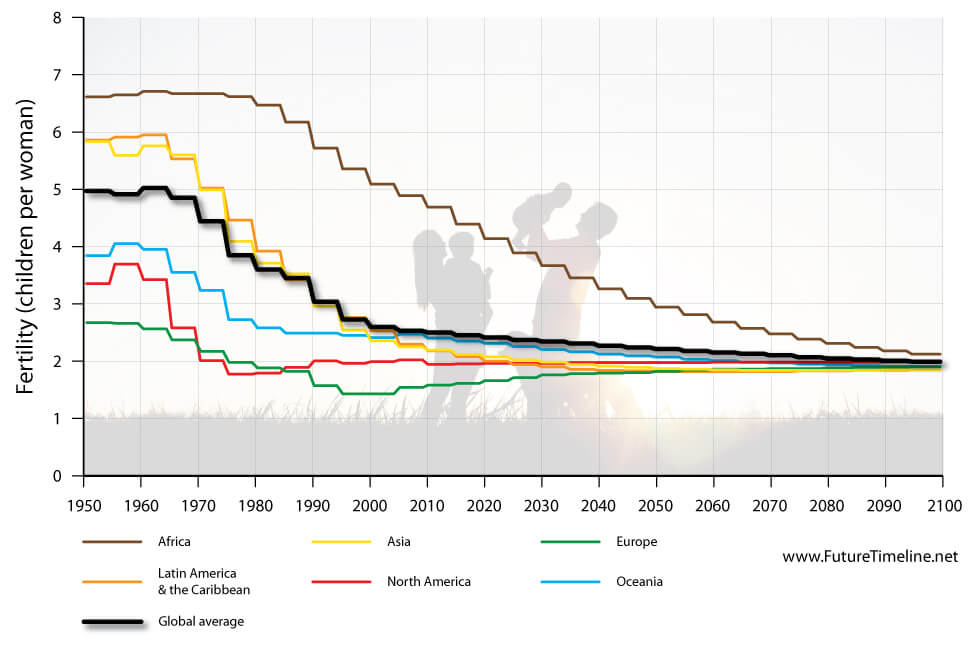

Global fertility has stabilised at below 2.0 children per woman

By 2095, the global average number of children per woman has dropped below two, with even Africa now approaching this level after 130 years of declining fertility.* There is now a remarkably similar rate between all regions on Earth – due to a range of factors including better education, improvements in health and living standards, access to contraception and shifting cultural perceptions on the value of children, ideal family size, etc.

Many of the world's languages are no longer in use

Increased globalisation has resulted in the number of human languages declining from around 7,000 during the late 20th century, to less than half of that figure now.* Many old sayings, customs and traditions have been abandoned or forgotten as the world becomes an ever smaller and more interconnected place. Changing social and economic conditions have forced many parents to teach their children the lingua franca, rather than obscure local dialects, in order to give them a better future. This is especially true in Africa and Asia.

This broad homogenisation of culture has been further propagated by the stunning advances in technology which have swept the world. Many people in developed countries, for instance, are eschewing their native tongues altogether, relying on brain implants for everyday communications. The young especially are utilising this form of digital telepathy, now sufficiently advanced that verbally speaking has almost become an inconvenience, due to the longer time intervals required in conversations.

Meanwhile, tribes people and isolated communities have lost homelands due to climate change, deforestation and shifting land uses. This forced migration and assimilation into the wider world has caused many ancient and rural languages to fade away. English, Mandarin and Spanish remain the lingua franca of international business, science, technology and aviation.

© Franz

Pfluegl | Dreamstime.com

2099

Sea levels are wreaking havoc around the world

Despite efforts to halt climate change, it came too late to save many lowland areas of the world. Sea levels rose almost two metres by the late 2090s, displacing hundreds of millions of people.* The Maldives were especially hard hit, with most of the nation disappearing underwater.* Countries around the globe were forced to begin large-scale evacuation and resettlement programmes, while trillions of dollars were spent on coastal defences.

Florida sea level rise. Credit: NASA

Over 80% of the Amazon rainforest has been lost

Due to the combined impacts of logging, drought, forest fires, desertification, agriculture and industrial expansion, less than one-fifth of the Amazon now remains.* In addition to mass extinctions of flora and fauna, many indigenous peoples' communities have vanished.

A portion

of the Amazon rainforest, 2000-2012. Animation created by Will Fox, using

imagery from NASA.

All newborns have a median artery of the forearm

By the end of this century, micro-evolution of the human forearm has resulted in all newborns now having a persistent median artery. This biological anomaly had once been considered an embryonic structure, normally regressing by the 8th week of gestation. In the womb, it functioned as the main vessel supplying blood to the forearm and hand, but would disappear once the radial and ulnar arteries developed in parallel on either side of it.

However, an increasing prevalence in adults began to emerge from the 18th century onwards. More and more people retained all three of the arteries throughout their lives. By the end of the 19th century, more than 10% of newborns had the feature and this had grown to 30% by the year 2000.

A study of cadavers in 2020 showed the phenomenon continuing, now observed in 35% of the population. Scientists attributed this micro-evolution to mutations of genes involved in median artery development, or health problems in mothers during pregnancy, or both.

Furthermore, studies revealed humans to be evolving generally at a faster rate than at any point in the past 250 years. Other changes in anatomy seen over a relatively short time included the increasing absence of wisdom teeth (caused by modern diets and a narrowing of faces), abnormal connections of two or more bones in feet, and the growing prevalence of spina bifida occulta (a small gap in one or more vertebrae).

By 2099, the persistent median artery is no longer considered a variant, but a "normal" human structure.* The extra blood vessel poses no health risk and actually provides a small benefit by increasing overall blood supply. It can also be used as a replacement in surgical procedures for other parts of the body.

The median artery of the forearm, an example of micro-evolution in humans.

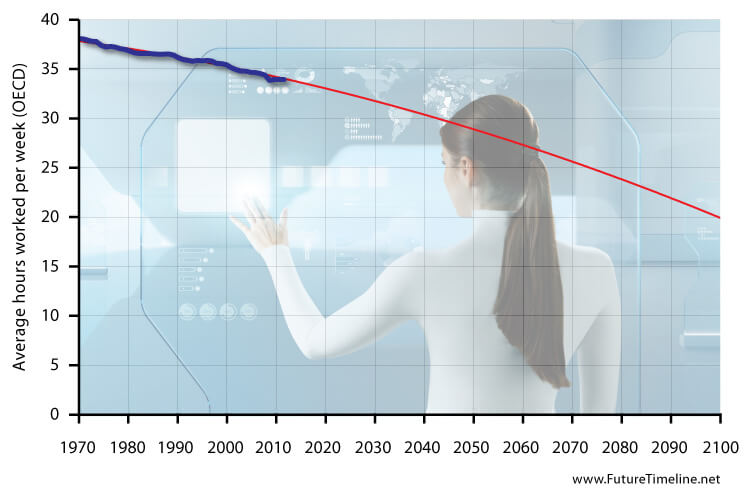

The average employee works less than 20 hours per week

In the early 1800s, most people in America and Europe worked shifts of 70-90 hours per week, or even longer during busy periods.** Conditions were often cramped and dangerous, pay was low (or non-existent in the case of slaves) and workers had little in the way of rights.

Later in the 19th century, a growing labour movement led to improved workplace regulations. A series of laws were introduced to improve safety and to limit the hours worked by employees – particularly women and children – while slavery was abolished throughout much of the world.

Further progress was made in the 20th century with the introduction of minimum wage laws, the emergence of five-day workweeks and continued growth in union membership. In 1900, a typical U.S. citizen worked 57 hours per week and this had fallen to 49 hours by the 1920s. Working hours fell sharply during the Great Depression, especially in manufacturing, but rebounded during World War II.

In the post-war boom years, the average length of workweek in the U.S. continued to fall, but at a slower rate than before, hovering at around 40 hours. There was a faster decline in Western Europe, however, and in the OECD as a whole. On both sides of the Atlantic, union membership declined substantially in the 1970s and 80s, though progress continued to be made in employment law.

In the 21st century, these trends continued. In the first few decades, this occurred alongside further changes in the workforce, with telecommuting and flexible business hours making work in developed nations more dependent on worker preference and efficient productivity.* In addition, this period witnessed the gradual loss of traditional labour as computer intelligence and automation proliferated.* This led to serious disruption as employers attempted to adapt productivity to the growing surplus of workers.

The growth of personal manufacturing in the form of 3D printers and nanofabricators, alongside increasingly common means of local power generation, began to significantly alter the economy itself. As production became more and more decentralised, work became less and less of a requirement for basic living. Spending on necessities like food at home, cars, clothing, household furnishings and utilities – as a share of disposable functional income – had already declined from 55% in 1950, to under 35% by the 2010s.* With such items becoming producible on a personal and community scale, work hours in many places were gradually becoming a matter of choice rather than need.

This revolution in manufacturing, combined with exponential growth of computer intelligence, would eventually change the nature of work itself. With an ever-growing share of the economy based on information technology, the average job was becoming more creative, personal and intellectual. By the latter half of the 21st century, artificial general intelligence had penetrated much of the business world, allowing workers to share tasks with computers able to operate with little or no human intervention.

Finally, a gradual cultural shift – in which more value was placed on free time and creative pursuits rather than work or material gain – began to emerge during the last decades of the century.* This grew largely out of the global response to climate change, but was also a consequence of technological advancement and the mounting costs of unchecked materialism. While by no means a rapid or ubiquitous trend, this also helped to reduce the need for traditional working jobs.*

All of these factors contributed to an ongoing net reduction in global working hours. By the 2040s, the average workweek had fallen below 30 hours. This trend continued, falling below 20 hours during the closing years of the 21st century.*

« 2089 |

⇡ Back to top ⇡ |

2100 » |

If you enjoy our content, please consider sharing it:

References

1 The Next 500 Years, Christopher Mason:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/659460/the-next-500-years-by-christopher-e-mason/

Accessed 16th August 2021.

2 Author Talk: The Next 500 Years by Christopher E. Mason, YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DWcs9EoamI

Accessed 16th August 2021.

3 The Next 500 Years, Christopher Mason:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/659460/the-next-500-years-by-christopher-e-mason/

Accessed 16th August 2021.

4 What if humans had photosynthetic skin?, Live Science:

https://www.livescience.com/what-if-humans-had-green-skin-photosynthesis.html

Accessed 16th August 2021.

5 British Social Attitudes Survey:

http://www.britsocat.com/Marginals/RELIGION

Accessed 6th October 2013.

6 "Swiss company Acabion sees such vacuum tube-based mass transport systems becoming a reality by 2100 and ... envisages a global network that would let users circle the globe in less than two hours and make transcontinental journeys possible in less than the time it currently takes to get across town."

See Around the world in 0.083 days: Acabion's vision for future transport, gizmag:

http://www.gizmag.com/acabion-streamliner-future-tube-transport-system/17735/

Accessed 14th February 2013.

7 "...China should target the development of high-speed ground transportation with 600 to 1,000 kilometers per hour which should be in operation between 2020 and 2030."

See Maglev Trains – Future of Transportation, Maglev.net:

http://www.maglev.net/news/maglev-trains-future-of-transportation

Accessed 3rd January 2018.

8 "If ETT does see the light of day it is estimated to travel at a top speed of 4,000 mph. That's more than mach 5! More than only the fastest record-breaking jets! At 4,000 mph, a trip from Washington DC to Beijing would take just two hours."

See From D.C. To Beijing In 2 Hours – Evacuated Tube Transport Could Revolutionize How We Travel, Singularity Hub:

http://singularityhub.com/2012/04/26/from-d-c-to-beijing-in-2-hours-evacuated-tube-transport-could-revolutionize-how-we-travel/

Accessed 14th February 2013.

9 Land_speed_record_for_rail_vehicles – Maglev_trains, Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_speed_record_for_rail_vehicles#Maglev_trains

Accessed 14th February 2013.

10 Extrapolated from the following dataset, and based on a Gompertz trend.

Age-standardized rate (World) per 100 000, mortality, both sexes, Australia + Austria + Canada + France (metropolitan) + Greece + Hungary + Ireland + Italy + Japan + The Netherlands + Singapore + Spain + Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA – Colorectum, Cancer Over Time:

https://gco.iarc.fr/overtime/en/dataviz/trends

Accessed 18th September 2025.

11 SpaceX launches Falcon Heavy rocket, Future Timeline Blog:

https://www.futuretimeline.net/blog/2018/02/6.htm

Accessed 16th February 2018.

12 Elon Musk’s Tesla will have a close encounter with Earth in 2091, SpaceFlight Now:

https://spaceflightnow.com/2018/02/14/elon-musks-tesla-will-have-a-close-encounter-with-earth-in-2091/

Accessed 16th February 2018.

13 How to survive the coming century, NewScientist.com:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg20126971.700-how-to-survive-the-coming-century.html

Accessed 25th May 2009.

14 Offshore Wind Is Taking Off in America, Greentech Media:

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/offshore-wind-takes-off-in-america

Accessed 13th August 2018.

15 List of offshore wind farms in the United States, Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_offshore_wind_farms_in_the_United_States

Accessed 13th August 2018.

16 Offshore wind farms coming to California — but the Navy says no to large sections of the coast, The San Diego Union-Tribune:

http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/business/energy-green/sd-fi-offshore-wind-20180506-story.html

Accessed 13th August 2018.

17 National Offshore Wind Strategy, BOEM:

https://www.boem.gov/National-Offshore-Wind-Strategy/

Accessed 13th August 2018.

18 Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States, U.S. Department of Energy:

https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/wv_chapter3_impacts_of_the_wind_vision.pdf

Accessed 13th August 2018.

19 Page 62 of report:

Offshore wind, Global Wind Energy Council:

http://gwec.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/offshore.pdf

Accessed 13th August 2018.

20 Offshore wind farms could tame hurricanes before they reach land, Stanford-led study says, Stanford University:

https://news.stanford.edu/news/2014/february/hurricane-winds-turbine-022614.html

Accessed 13th August 2018.

21 Taming hurricanes with arrays of offshore wind turbines, Nature:

https://www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2120

Accessed 13th August 2018.

22 Kardashev scale, Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kardashev_scale

Accessed 13th August 2018.

23 Total fertility (TFR), World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs:

http://esa.un.org/wpp/Excel-Data/fertility.htm

Accessed 14th September 2014.

24 Dying languages to be preserved in talking dictionaries, The Independent:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/dying-languages-to-be-preserved-in-talking-dictionaries-7079788.html

Accessed 14th September 2014.

25 All Wet on Sea Level – The Remix, YouTube.com:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kffsux-ifKk

Accessed 24th September 2009.

26 Maldives cabinet makes a splash, BBC News:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/8311838.stm

Accessed 17th October 2009.

27 No rainforest, no monsoon: get ready for a warmer world, New Scientist:

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn17864-no-rainforest-no-monsoon-get-ready-for-a-warmer-world.html

Accessed 28th February 2010.

28 Forearm artery reveals humans evolving from changes in natural selection, EurekAlert!:

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2020-10/fu-far100620.php

Accessed 28th February 2021.

29 Hours of Work in U.S. History, EH.net:

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/hours-of-work-in-u-s-history/

Accessed 9th February 2014.

30 British society – 1815-1851 > Living and working conditions, BBC:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/history/shp/britishsociety/livingworkingconditionsrev1.shtml

Accessed 15th October 2013.

31 We're Getting Off the Ladder – The Future of Work, Time:

http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1898024_1898023_1898076,00.html

Accessed 15th October 2013.

32 See 2039.

33 Spending on food at home, cars, clothing, household furnishings and housing and utilities, as a share of disposable functional income, 1950-2012, US Bureau of Economic Analysis:

http://imgur.com/BWB95oN

Accessed 15th October 2013.

34 See 2060-2100.

35 Working hours: Get a life, The Economist:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/09/working-hours

Accessed 15th October 2013.

36 Average annual hours actually worked per worker, OECD:

http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=ANHRS#

Accessed 15th October 2013.

![[+]](https://www.futuretimeline.net/images/buttons/expand-symbol.gif)